Many mega-challenges are causing the world to stagger.

A third world war “in instalments” is taking place, as Pope Francis said repeatedly, and just as Pope Leo once did.

I am fearful that we are once again beating ploughshares into swords and no longer pursuing the goal of becoming fit for peace, but rather for war.

The images of children emaciated to skeletons cry to heaven in the sense of the First Testament. The nightly bombing terror in Ukraine also bears the marks of a war crime.

Then there is the climate emergency, which IPCC experts deem alarming because we are approaching irreversible tipping points ever more rapidly, thereby losing control over maintaining a stable climate system.

Many people are also unsettled, often overwhelmed by migration. In some municipalities and schools, this seems to be growing beyond their capacity to cope and is dampening the willingness, which is certainly there, to offer active help.

Fear makes people cruel.

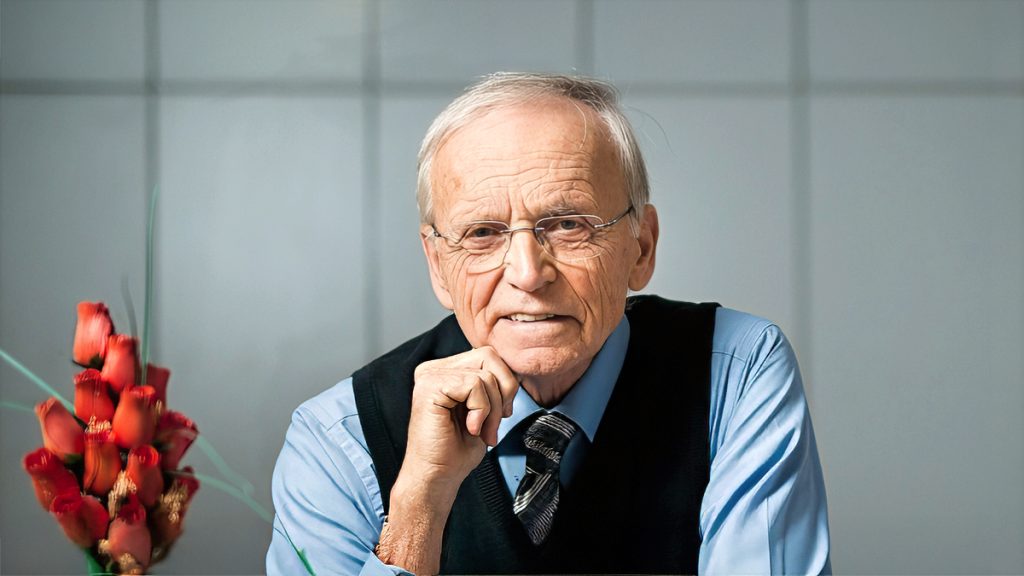

Paul M. Zulehner

It dissolves solidarity.

It creates a culture of rivalry.

Fear and the politics of division

In the wake of such challenges, fear grows. Our societies seem to be running out of resources for hope. The staggering of the world breeds anxiety and concern. Moreover, many of us are troubled by the fact that political populists and religious fundamentalists deliberately amplify this fear and shamelessly exploit it for electoral gain.

Fear, however, makes people cruel. It dissolves solidarity. It creates a culture of rivalry. We defend ourselves against our own fear through violence, greed, and lies.

Reading the signs of the times

As a theologian, I am not satisfied with merely describing the situation. I want to interpret it from God’s perspective as a sign of the times, through which God enlightens our understanding and inspires our actions.

I am concerned that, in the process of bidding farewell to the Constantinian era, Christian churches, preoccupied with structural change, including synodality, are so absorbed that we have hardly any time or energy left for a sound theology of the world.

It would be a nightmare for me if, before long, the Church were perfectly reformed (including women’s ordination) and yet the world continued to stagger toward the abyss.

We defend ourselves

Paul M. Zulehner

against our own fear

through violence,

greed, and lies.

God’s passion for creation

In seeking a theology of today’s world, I have long been moved by a quotation from the Old Testament prophet Joel about God’s passion for his land. I understand this as his passion for his world, even, and especially, when it is staggering.

God remains steadfastly faithful to it (Deut 32:4). The rainbow is the sign of this. It already made the disembarkation from Noah’s ark after the ecological disaster of the great flood into the first rainbow parade.

In 1941, Maria-Luise Mumelter-Thurmair, born in Bozen, wrote the hymn The Spirit of the Lord Fills the World (GL 347) to a melody by Melchior Vulpius (1609). It recalls the omnipresent work of God’s Spirit throughout all history.

This work of the Spirit operationalises God’s passion for his world. From the Big Bang onwards, God has been constantly creating through his Spirit, what theology calls creatio, more precisely nativitas continua.

Teilhard de Chardin intuited that God’s Spirit of love is the driving force of evolution towards its fulfilment. His grand vision is echoed in modern science.

God’s love finds resonance in the sociologist Hartmut Rosa and the neuroscientist Joachim Bauer. Or, to put it in the musical language of this city’s genius, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: this makes world history into an ongoing symphony of creation in which everything participates and everyone plays a part.

The world’s staggering today

Paul M. Zulehner

is no reason

for the doom-saying

of ‘calamity howlers.’

Choosing hope over defeatism

The world’s staggering today is therefore no reason for the doom-saying of “calamity howlers” — to honour my favourite pope, John XXIII. He was convinced the world is not as bad as some fundamentalist Catholics would like it to be to enhance our saving importance.

Roland Schwab, director of Tristan und Isolde, observed: “We can smell the apocalypse right now.” But precisely that inspired him to open up a space of longing in the theatre that drives away apocalyptic defeatism.

Still, pointing out the world’s staggering is a call to urgency, to resolute action, urgently required; in cooperation with the best minds in art, culture, science, and politics.

Such collaboration could lay the foundation for a politics full of confidence and trust, which could push back the disastrous “politics of fear” described by Ruth Wodak.

Angela Merkel’s “We can do it” may sound presumptuous, but theologically, it is an appropriate statement.

For if God has passion for the world, realised in the work of his Spirit, and we are his agents, who then can be against us?

Those possessed by violent, deceit-ridden fantasies of great power and greed for wealth and influence — now increasing worldwide with incredible brazenness — will fail.

If God has passion

Paul M. Zulehner

for the world,

realised in the work

of his Spirit,

and we are the Spirit’s agents,

who then can be against us?

Psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer once remarked about Adolf Hitler and psychopaths marked by delusions of divinity and an insensitivity to suffering: “In good times we treat them; in bad times they rule us.”

Wilfried Haslauer was spot on when, citing Stefan Zweig and Heimito von Doderer at the 2023 Salzburg Festival, he said: “The demons are loose, in us and around us.” But precisely when the devil is literally on the loose, God’s passion for his land is all the more awakened. The time of demons is also a time of the Spirit of God.

Seeing the Spirit at work today

Whoever sharpens their spiritual vision cannot fail to see the work of the Spirit today: the Spirit’s work is evident in the widespread longing of so many people for peace, for justice, for a shared world in which one can drink the water and breathe the air without harm, and where the bees do not die — because, as Albert Schweitzer warned, this would mean the end of humanity in a short time.

God’s saving Spirit is revealed in the countless people who, personally and politically, are committed today to peace, to the preservation of creation, and to justice.

I think of the United Nations and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). I think of the founding fathers of the European Union who, inspired by the Spirit of the Gospel, laid a foundation for peace, for a “green deal,” and for a human-rights-compatible migration policy.

God’s saving Spirit

Paul M. Zulehner

is revealed

in the countless people

who,

personally and politically,

are committed today

to peace,

the preservation of creation, and to justice.

And where, in all this world activity, is the place of those who see themselves as followers of Jesus and members of that movement that still bears the honourable name “Church”, a name darkened by our shameful sins, yet whose light they cannot ultimately extinguish? It is the same Church from which we sometimes wish to slip away, ashamed and embarrassed, only to find ourselves, like the prophet Jonah, fleeing from God, reluctantly sent into the seemingly secularised Nineveh, “a city with more than 120,000 people — and so much cattle besides” (Jon 4:11).

Learning from Jesus’ Kingdom-of-God movement

To clarify the role of the Christian churches in today’s tumbling world, it is worth looking at Jesus and the NGO he founded, the Jesus movement.

I take a biographical approach.

At the age of six, I learned in religion class from the Small Catechism of the Catholic Faith. It consisted of questions and answers. We were required to memorise them, typically German; the French learn par cœur!

The first question was: “Why are we on earth?” The answer: “To know God, to love him, and to serve him, and thus to come to heaven.”

This programme shaped the religious practice of my childhood.

Jesus

Paul M. Zulehner

did not teach his followers

to pray,

“Let us come

to your kingdom,” but

“Your kingdom come!”

Later, during my studies, I came across a saying of the Aachen bishop Klaus Hemmerle (1929–1994): “We Christians are not on earth to go to heaven, but so that heaven may come to us.”

That turned my faith upside down.

With the Council, and my teacher Karl Rahner, I learned to hope that God would ultimately save everyone, Stalin, Hitler, and me, as Rahner provocatively put it in lectures.

I thus learned to leave the “going to heaven” up to God. But my growing spirituality also led me to see that God and his heaven are not ahead of me — the world is ahead of me, with God’s Spirit-wind at my back.

I realised that Jesus did not teach his followers to pray, “Let us come to your kingdom,” but “Your kingdom come!”

That, then, was Jesus’ mission: to sing heaven down to earth. The world was to become more like the Kingdom of God — more heavenly.

The preface of the Feast of Christ the King praises this kingdom as the “kingdom of truth and life, the kingdom of holiness and grace, the kingdom of justice, love, and peace.”

That, I believe, is the contribution of Christians in today’s tumbling world: to bring heaven to earth, if only in traces, I add humbly.

That is precisely what I mean when, in the title of my political meditation, I speak of gifts of heaven for a tumbling world.

A more heavenly world is a more human world.

The gifts of heaven

These, then, are important gifts of heaven.

The first: all being is one. Aristotle, Bonaventure, and even Ken Wilber express this wisdom of the unity of all being in the image of a “chain of being,” stretching from stone to God.

Crude nationalism stands in stark opposition to this. There is only one world, one human family.

If all shares in the one, ultimately divine, being, then there is a fundamental equality of dignity for all. This also requires that we speak not of an exploitable environment, but of a fellow-world (Mitwelt) to be cherished.

This equality of dignity is contradicted (as Gal 3:28 states) by humanity’s age-old discriminations: the racist (between Jew and Greek), the economic (between slave and free), and the sexist (between male and female and other variations of sexual orientation).

This comprehensive prohibition of discrimination is not only a theologically explosive gift within the Church, but also a politically urgent one in times of resurgent antisemitism and anti-Islamic sentiment. Agere sequitur esse: from being flows action. From the one being derives the categorical imperative of universal solidarity.

If five-year-old Aylan Kurdi drowns in the Aegean seeking asylum, then one of us has drowned — and it concerns us. The division of the world into rich and poor cries to heaven. And if people flee war, natural disasters, and hopeless poverty, they have the right to be received, while we have the duty, through generous development cooperation, to ensure they do not need to flee.

It is unacceptable that armaments kill the poor.

In times of growing fear, one of the greatest gifts of heaven is to unlock buried resources of hope.

“‘The world’ needs no doubling of its hopelessness by religion; it needs and seeks (if anything) the counterweight the explosive power of lived hope,” says the marvellous 1975 Würzburg Synod document Our Hope, shaped by Johann B. Metz.

Christians could be, in our fear-driven world, like partisans of hope, or better, midwives of hope.

Everything that fosters trust serves the goal of becoming “of good hope”: parents who create bonds, schools that provide education, and a politics of trust that deprives fear-based politics of its power.

Politically partisan for the Gospel

Finally, the question remains: how can we as churches give the world such gifts of heaven and thus become a blessing for it?

On this vast topic, just a few aphoristic remarks.

Shouting commands such as “make peace,” “protect nature,” “care for the vulnerable,” “be in solidarity,” “do not be afraid” rarely help.

Pope Francis has written moving encyclicals on all these challenges. He has joined with leaders of other religions to issue joint statements. His successor, Leo XIV, has so far kept pace with him.

Yet such calls fall on deaf ears and closed hearts among the Trumps, Orbáns, Ficos, Mileis, Erdoğans, and Putins. Still, might it not happen, I speak against my fears, that God opens the ears of their hearts, just as he enabled Lydia, the purple dealer from Thyatira, to listen to Paul’s preaching (Acts 16:14f.)?

It seems more effective when Christians first see themselves as members of the human family.

As such, God calls them to the eucharistic celebration.

There, as Benedict XVI taught, World transformation can happen: if not only the gifts, but also the gathered are truly transformed, then violence is turned into love, fear into hope; and with these transformed people, the world itself begins, even if only in part, to be transformed.

The final document of the 2024 Synod even contains the fascinating idea that religious orders or universities could be “laboratories of the Kingdom of God” in the midst of the world. This could also be an apt description of the Christian churches themselves.

Decisive for making the world more heavenly through the service of the churches could be that the baptised, filled to the brim with the Gospel, engage with professional competence in shaping society. I

mean Christians who work with expertise in education, in art and science, in business, or civil society.

This applies no less to politics at every level: in municipal councils, national parliaments, the Council of Europe, and the United Nations.

Such Christians know that their Church is not a political party, but is politically partisan.

They do not make “Christian politics,” but rather test, even in different political parties, whether their ideas align with the Gospel they carry within them, or whether they are challenged by it to realign.

They do this, thanks to their broad ecumenical spirit, together with seekers, agnostics, and good-willed atheists.

Thus, “catholic” expands from denominational to universal.

This catholic breadth rests on the conviction that God’s creative and saving Spirit is not given only to the baptised.

A verse from Maria-Luise Mumelter-Thurmair’s hymn may poetically sum up what I have tried to suggest in this political meditation:

The Spirit of the Lord

Maria-Luise Mumelter-Thurmair’s hymn

sweeps through the world,

mighty and untamed;

wherever his breath of fire falls,

God’s kingdom comes alive.

Christ strides through the ages

in his Church’s pilgrim garb,

praising God: Hallelujah.

- Paul M. Zulehner is a professor emeritus of pastoral theology at the University of Vienna. He is the author of more than 50 books.

- Translated from German. Republished with permission.